“You have the wrong hospital.”

These words greeted me the first time I drove up to the gate of Mbabane Government Hospital (MGH).

“The private hospital is across town,” the guard continued.

“No, no, I am a doctor coming to work here in Mbabane, and I want to see the hospital.”

“You are not here for sickness?”

I wasn’t sure how to answer that question. Sickness was certainly involved in my decision to leave the United States, join the Pediatrics AIDS Corps in Swaziland, and find my way to Mbabane’s primary pediatric referral center.

“I am not sick, but will be working with many of the sick children here.”

That was quite some time ago, and I have indeed worked with many of the sick children here. This past week, after nearly three months of working primarily in the outpatient HIV clinic supported by Baylor, I spent a few days at MGH seeing patients alongside the doctors and nurses there.

While it is still fresh on my mind, I wanted to offer you a short, virtual tour.

The pediatric ward of Mbabane Government Hospital is known as “Ward 8”.

Just before you enter this ward, there is a large ORT/Nutrition room to the right, where children spend the day if they need oral rehydration (the T in ORT stands for “therapy”).

Children present to Ward 8 for many reasons, but among the most common is diarrhea, malnutrition or both. This is not an easily-solved problem, considering that children are usually subject to an unsafe water supply and food insecurity for a long time before arriving to Mbabane Government Hospital. Recuperating from a long-term, progressive condition requires time, and it is difficult to ensure that a severely malnourished child gains weight. For this reason, the ORT/Nutrition room is staffed by two very kind nurses to oversee this process. One of these nurses is named Happiness. If you find yourself entering Ward 8, pop in to tell her hello, for she is appropriately named.

As you enter Ward 8, you will notice that it is bisected by a long hallway. There are three large rooms off the hallway to the right, and there are several smaller rooms off to the left. The first door you reach is on the left, and it is the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). To those trained in academic centers in the developed world, intensive medicine is defined by supporting fundamental physiologic functions, like, for example, helping a child to sustain dropping blood pressure, maintaining electrolyte balances when the body’s regulation falters, mechanically filling the lungs with air when a child cannot do so on his or her own, or even monitoring and controlling the pressure inside of a child’s skull to prevent brain loss or death after trauma (usually mechanical) to the central nervous system.

In Ward 8, intensive care means something quite different. The 4-5 children in the PICU at any given time are those that most need oxygen, for there are functioning O2 ports built into the wall of this room, a rarity in other locations. Beyond this limited support, in addition to standard IV fluids and possibly medications from the hospital’s strained pharmacy, the child must maintain her or his own vital signs. In many cases, the children do. In the cases where they do not, another death follows, in most cases a preventable one.

If you continue down the hallway of Ward 8, you will pass a small workroom on the left, where nurses and doctors congregate when not at the bedside. The room is plain, with only various bulletins adorning the walls, many from past HIV/TB public health campaigns.

If you find yourself peering in this room, you may notice that uniformed nurses within eye you suspiciously. Don’t mistake it for hostility. This is the look they give the “short-termers”. Rare is the visitor to Ward 8 that stays longer than a few days or weeks. Most new faces, I would guess, stay but a few minutes, seconds even.

Don’t get me wrong. Short-termers care immensely for the children in Ward 8, and they want to help, to make things better, to change things. They are usually deeply moved by what they see on the ward. I suspect you will be too.

I know about short-termers because I have spoken to them as they wander through Ward 8. I know about them because I myself am one.

The nurses are not short-termers. They went to nursing school because they too want to make things better in Swaziland, and they want to do it for a living. Most of them are Swazis, and were trained at the local university. The Swazi nurse uniform they receive at the end of this training is more like a military garment than the cheery, flowery scrubs that U.S. nurses wear. The Swazi nurses wear their uniforms proudly.

They can be found in Ward 8 every day, in uniform. They see a child die on many of those days. There is little cheer in this, and usually little they can do about it. There are around a dozen nurses that rotate through Ward 8, but only two or three on at a time. The average patient census is around forty, the children are often very sick, and supplies are few.

Between checking on the 25 sick children under their care, they might look at you suspiciously, but don’t take it personally. It is just that they have heard the short-termers’ words of encouragement, the promises, and still, a year or more later, they are working in an ill-equipped, crowded ward, except this year the ward is slightly more crowded because more children are presenting with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

You see, HIV treatment for kids, available for many years in rich countries, is just now becoming consistently available in Swaziland. As the Baylor clinic and its partners scale up such treatment, the inpatient pediatric census will likely drop substantially, but for now up to 80% of the children are HIV-positive.

Though I would like to promise the Ward 8 nurses that we will decrease the number of children in the hospital, I refrain. They would only eye me suspiciously, and rightly so. I have been in the hospital a total of four days, in Swaziland for three months. I am a short-termer.

Continuing down the hallway, we come to Cubicle #1, the first large room on the right. Before entering, you can see through the glass panels that there are approximately 12 cribs lining the walls, except for the far back corner which has a long platform with dividers, where infants can be laid side-by-side. Up to three patients can be assigned to each crib, but usually there are only one or two. Beds are shuffled around as needed for older patients.

The room itself is not unpleasant. It is recently painted, with at least some perceivable ventilation through the back windows. The temperature in the room, as a result, is actually agreeably temperate. The primary smell is faint and is that of kerosene, which is sometimes used as an antiseptic for the floors.

Each child is coupled by a caregiver (usually the mother, aunt, or grandmother), who provides for the child’s basic needs. The hospital provides the food (though the formula supply is sometimes interrupted), and the caregiver feeds the child. The nurses’ role is to administer medications, troubleshoot and coordinate patient care with the doctors.

Cubicle #1 is reserved for kids with infectious disease diagnoses. Most of the patients have a respiratory ailment (pneumonia, tuberculosis, asthma, etc.), but diarrhea, meningitis, and others are not uncommon.

Neighboring Cubicle #1 is Cubicle #2. It is reserved for surgical patients. Children recovering from accidental trauma—complicated burns, fractures, etc.—are monitored here. (Such trauma is not uncommon in Swaziland, given open-flame cooking, lax traffic laws, and the density of pedestrians along major roadways.) Children with other surgical needs (intestinal obstruction, ostomy revision, appendicitis, mitral valve insufficiency, etc.) are also assigned to Cubicle #2.

As you arrive at Cubicle #3, you will notice a small mural on the left. The painting depicts many of the characters from Disney’s The Lion King. It is nice to look at, and seems to be the project of a former short-termer, as it is beginning to show signs of wear.

Cubicle #3, the last door on your right, is for chronic patients, namely those that need intensive nutrition or long-term antibiotic therapy. They are segregated from Cubicle #1 to control infection as much as possible, but patients with TB (diagnosed and undiagnosed) can end up in any room.

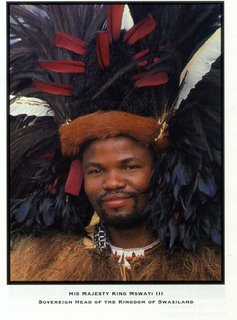

Swaziland has the highest rate of TB in the world.

The cubicle system is certainly not perfect, but lest you find yourself surprised by this, I will point out that Ward 8 does not always have running water, much less soap. N-95 masks, HEPA filters, negative-pressure rooms, individual patient isolation are science fiction here at MGH, regardless of your TB status.

On that note, if you want to diagnose military TB or TB of the spine, you have to do so without cross-sectional diagnostic imaging. Pictured below is the local government hospital's cat scan machine. It broke some time ago and there are neither the parts or the expertise to fix it. The elevator met a similar fate, so the cat scanner was placed where pictured to keep patients from entering in the stagnant elevator car.

This brings us to the last door on the tour. Through the door there is a small room, about five square meters. Some call the room the “laundry room”, for indeed it is where the sheets and other linens are washed. I have heard others call it the “room for abandoned children.” Indeed, the room is also full of children without a home.

The children are between 1 month and ~10 years of age, and most appear relatively healthy (though a good proportion are suspected to be HIV positive). They all have different stories. Some are orphans. Some are developmentally delayed. Some just moved over from Cubicle #3, having nowhere else to go, and nobody to go to. Regardless of the events leading up to their confinement to the back of Ward 8, they were now under the care of a few dedicated women who feed, change, and clothe them between loads of laundry.

This concludes your tour.

--

Any walk through of Ward 8 forces the walker to ask difficult questions. I am not an expert in asking difficult questions, and am the most amateur of amateurs in offering meaningful answers to these questions. Such answers, I might add, are well beyond the scope of this blog, and well outside of my zone of personal comfort.

With that said, I will quickly address one question that often nags me when I am faced with unnecessary childhood suffering and death. The question is this: When a child suffers or dies a preventable death from a treatable disease, is it because that child is less valuable to those in charge of protecting him or her from harm?

My answer: No.

As I see it, there is a difference between the capacity to love and care for another human being and the capacity to intervene. I have seen too many desperate, mournful mothers and fathers to believe that indifference blunts the pain when a child hurts or dies.

Love and care are fundamental to humankind, and they cost nothing. Intervention, on the other hand, is not free. The capacity to love and feel is inborn, but the capacity to place a child who cannot breathe on a ventilator is not. It is expensive.

Rare is the society that can support high-dollar intensive care medicine for children.

Very rare is the society that does not wish to defend the health of children and does not wish for a state-of-the-art children’s ward and PICU.

Extrememly rare is the opportunity to have wishes come true when you live in a country where the vast majority are feeding, clothing, and sheltering their family on little more than a dollar a day.

--

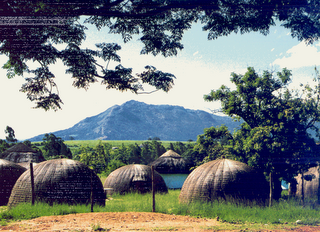

Yesterday, a Swazi told me a story about a group of four children he came across near his small village in the hot, dry eastern lowveldt of Swaziland. The oldest was approximately 10 years of age, and she was accompanied by three younger siblings. The 10 year-old was wearing underwear, and the others were completely nude.

The four naked children, he explained, had been walking for 30km looking for their grandmother. Their mother had died the day prior, and the oldest child had led them on a search for their nearest known relative.

The 10 year-old was confident that they were almost there.

--

My answer to the above question is “no” because I am certain that the mother of these 4 children did everything she could while alive to ensure that her children would not have to walk nude and aimlessly across arid countryside in search of someone to feed, shelter, and clothe them. She did all she could, but it was not enough.

Poverty and sickness did not make her care less. Poverty and sickness took away her ability to protect her children from becoming orphans with no place to go.

To understand Ward 8 and the values assigned to the lives within, it is necessary to first understand this country’s poverty and the sweeping effect of HIV/AIDS among its people.

This understanding is not acquired over the short term.

Labels: Other stories