Teaching pathology - A training day

Teaching pathology: a training day

“How many here have done HIV trainings before?” Dr. Delouis asked. About three-quarters of the 28 community-based nurses in the room raised their hands.

“How about pediatric HIV?”

All hands sank.

“Okay,” Dr. Terlonge said. (I believe this response was short for, “Okay, well, at least we are in the right spot.”)

‘We’ were a group of four American-trained doctors. Three pediatricians and one preventative medicine specialist. We were from San Francisco, New York, New York, and Denison, respectively. That makes three city slickers and yours truly.

We were about to begin a 4 day pediatric HIV training course at the Piggs Peak Government Hospital, approximately one hour’s drive north of Mbabane, Swaziland. Nearly all nurses from the hospital’s catchment area were in attendance.

We were there because, as reflected by Dr Delouis’s informal show of hands, it has been the tendency of developing world HIV programs to focus on adults. They are, after all, the productive population that works and pays taxes. They are also the re-productive population that has sex.

Dr. Delouis explained that, as pediatricians, we were there to introduce them to HIV in kids, beginning with the epidemiology and pathophysiology of pediatric HIV, followed by diagnosis, care for the HIV positive pediatric patient, nutrition in HIV, prevention of maternal to child transmission, etc.

After Delouis spent an hour reviewing the magnitude of Swaziland’s epidemic (summary: very large in magnitude), it was my turn to speak. I was to discuss the pathophysiology of HIV in children (physiology being how HIV behaves and replicates; pathology being how it messes things up).

Physiology and patology talks can be quite boring, so I had been thinking about strategies to spin the topic to the audience in such a way that it seems more interesting.

I needed a hook, if you will.

My father’s name is Dr. Chuck Phelps. He is an avid fisherman, and he knows hooks well. He grew up near the lake with the best striped bass (or “striper”) fishing in the world (or at least I have been told this). I grew up there too. It is a lake called Lake Texoma, and it is called this because it was formed in 1942 when the Red River dividing Texas and Oklahoma was dammed.

For every striped bass in Lake Texoma, I estimate that there are at least three types of hooks that have been designed to get these fish from the water to the boat. My father knows them all. He knows when to use them (dawn, dusk, deep water, shallow water, northerly wind, southerly wind, and so on and so forth). He knows how to use them (reel in slow, reel in fast, make the lure splash, make it sway, make it dance, jiggle, sink, float, pop, slither, juke, bounce, slide, meander, pause, surge, pivot, shimmy, spin, roll over, play dead and so on and so forth). He know where to use them (near the dam, near the Lowe's Highport islands, near Eisenhower Marina, on the rocky Texas shore, on the sandy Oklahoma shore, and so on and so forth).

As far as the ‘why’, my father fishes because he likes spending time outdoors. He fishes with me because he likes spending time with his eldest son. He likes sharing his knowledge of the lake he grew up on. He likes to take fish home and fry them with potatoes and hushpuppies. He likes to sit down with his wife and three kids and share the fried striper he caught and prepared.

My father fishes because he likes to honor and relive the memories of doing the same with his father, my grandfather, who I never had the privilege of meeting. His name was Dr. Ray Phelps, and he was north-central Texas’ first pathologist.

He moved there because he liked the lake, and he wanted his kids to grow up in Denison, Texas. He moved there because there was no pathology department in the local hospital, and therefore no mechanism to routinely examine disease on a microscopic level, the level at which all disease operates. As Dr. Ray was an expert on the microscopic workings of disease, he received a warm welcome in Texomaland.

I didn’t have the opportunity to ask Ray why he become a pathologist, but I imagine he was interested (as I am) in how disease meddles with normal human physiology, how it interrupts the health and integrity of the human body, one tiny cell at a time. I wonder if Dr. Ray Phelps was moved (as I am) by the pain that these tiny pathologic malfunctions can inflict on a previously healthy human being, no matter how young. I wonder if somehow learning how all of the malfunctions look under the microscope offers some comfort that sick tissues might someday regain function.

It was time to start the lecture.

Still, no hook was coming to mind.

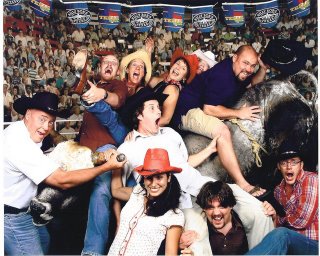

My first powerpoint slide was a photo of my extended family on the stuffed bucking bull in Ft. Worth, Texas’ “Billy Bobs”, the self-proclaimed largest honkey-tonk in the world. The photo, as shown, was taken on my recently elapsed 31st birthday.

“What does this make you think of?” I asked.

“Texas!” one of the participants shouted.

San Francisco has its Golden Gate. NYC has the Statue of Liberty. Texas has livestock and more swagger than you can fit in a ten-gallon hat. Eat your core out, Big Apple.

I explained to my audience that the topic I was about to cover had the potential to get a bit dry, and that I wanted to brainstorm with them about how to make it as interesting as possible.

I briefly reviewed my father’s love for fishing, and I brought up the idea of the hook.

“What would be the perfect hook?”

Whispering. More whispering

“Chocolate!” one of the participants proclaimed.

There is a particular chocolate here called “Tex”. It is basically like an oversized Kit Kat. There was a grocery store across the street where they were on special.

“Tex bars? It’s a deal.”

I divided the group into teams and asked them to choose team names.

They chose Team Texas vs. Team New York.

I kid you not.

I then explained that I would ask multiple quiz-type questions throughout my presentation. The team answering the most questions correctly would win Tex bars.

I started with a brief recap of the previous epidemiology lecture. I reminded them that nearly half of pregnant women in Swaziland are HIV positive.

“Do you remember the number?”

“42.6%!” one of the nurses said. Score 1-0, Team New York in the lead.

Boooo!

I reminded them that, without treatment, nearly half of HIV positive pregnant women pass the infection to their newborn child.

“What percentage?”

“About 40%!” Score 1-1.

I told them that HIV was retrovirus, meaning…

“It contains RNA!” 2-1

It is also a lentivirus, meaning…

“It is slow!” 2-2

“Exactly. This means that it lets its host live for long enough to infect others. As a

matter of fact, usually the infectious person has no idea that he or she is infected, for there are initially very few symptoms, and an individual can feel quite well while the virus slowly percolates, becoming stronger and stronger, like the coffee that awaits you as soon as we finish the lecture.”

I could hear the faint clicking of the tea-time percolator on the other side of the conference room door.

I continued to tell them how HIV thinks and acts. I told them how it enters cells, replicates, and then leaves to infect other cells. I told them how HIV destroys the CD4 cells that normally protect the human organism from infection.

They knew much of this. The score was 12 all.

I went into more and more detail and asked more difficult questions. When I ran out of powerpoint slides and difficult questions, the score was tied at 16-16.

I thanked them for being one of the more engaged, energetic audiences I had met (for indeed they were), and then assumed the more casual posture that one assumes to demonstrate that a lecture is finished.

“What about the chocolate?”

“But it was a tie.”

“Let’s have a tie-breaker!”

“Okay. A bonus question.”

I put up the photo of my family, and asked them to point out which one was my father.

They entire room exploded, with all participants pointing to the tall, wide-eyed man with a ten-gallon hat and the big grin.

“What is his name?”

“Chuck!” in unison.

His favorite lake and fish

“Lake Texas-Omaha! Striped sea bass!”

“Close enough.”

My grandfather’s name and profession?

“Dr. Ray! Pathologist!”

Still more or less a draw.

“We will just have to get enough for everybody to have one,” I said.

We adjourned for tea, coffee, Tex bars, and miniature tuna sandwiches.

I have been fishing with my father several hundred times. The last ocassion was just before moving to Africa. We left Eisenhower Marina when the sun was about a finger’s width above the western skyline, and we began to motor about in search of promising waters. The army of pied lures rattled in the three mega-tackle boxes at my feet, the water was glassy and reflected the late day’s light, similar in shimmer and color to coals beneath a dying fire. My father’s face wore an expression of determination, relaxation, and contentment. The horizon undulated as the boat hovered over the broad waves of the broadest stretch of the Red River, so named for the region’s crimson, iron-rich soil. The temperature was such that the moving air neither cooled nor warmed the skin as it passed.

There were no casts that evening. No lure left the boat, and no striped bass became fried Phelps-food. We just toured the spots where the fish might be, looking for splashes, birds, telling wind patterns. Finding none, my father and I spent the last hour of that day simply moving over glowing water at 35-40mph.

I have been fishing with my father several hundred times. No fishing trip has ever come close to that last one.

I bet it would have made my grandfather, Dr. Ray Phelps, proud to see his son and grandson that night, gliding over Lake Texoma, where he once lived.

Labels: Other stories

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home