Death on the river card - A patient encounter

“I am one confused citizen,” she said, slowly shaking her head. “Sometimes I just want to lie down and die with my baby.”

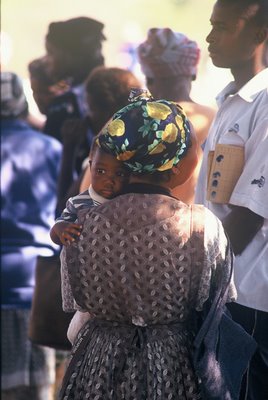

These were the words of my first patient in Africa. Her name was Thembela. She was HIV infected, as was my second patient in Africa, the baby she cradled in her arms. The baby swayed side to side in synchrony with the dejected mother’s bowed head. The baby was 13 months old, and already demonstrated signs and symptoms of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

Children acquire HIV during birth or while breastfeeding, with rare exception. If an HIV infected child’s fortune can be compared to a game of cards, the child’s hand is a 2-7, off-suit. If these two cards are placed face-down in front of you, you do not bet on winning.

This child was not winning.

Thembela’s hand was no better. She lived in a home where there where certain words that were never spoken, a home where certain topics of conversation were taboo, a home where 15 or so others lived, mostly in-laws. To bring up these unspeakable things was to risk being banished from the home altogether.

In Swaziland, a diagnosis of HIV brings with it great stigma. If you declare your status, you immediately embody everyone’s worst fear. You become a reminder to all who see you that they too could be dying and not even know it. Such reminders were forbidden in Thambela’s home.

The mother explained all of this to me, then looked at me blankly.

Texas Hold-em is a variation of 5 card draw. If you have not heard of it, you either do not have cable or have cable and have never surfed the second-tier sports channels. I like it because anybody can win. It is a game where seeming average makes you above average, and where almost every winner looks average. It is a game that reminds me of home.

My extended family stretches from just south of the Oklahoma border to Houston. When we get together, we play Texas Hold-em. We play for money, trophies, bragging rights, and pride. We play hard and late into the night. I have been here in Swaziland for a few weeks now, and I think fondly of those late nights. I think of the laughter, the companionship, the Shiner Bock, and what it means to be home, surrounded by loved ones.

Looking into my very first patient’s expressionless face, I realized that, for her, being home meant lying. It meant playing a losing hand as well as she could. It meant keeping a straight face while watching everything slip away. It meant bluffing until death.

“I am one confused citizen,” she said, slowly shaking her head.

I was one confused doctor. This woman could not take my medicines home, and she could not be seen taking them or giving them to her baby. She could not tell anyone she had ever been to our “HIV clinic”, and she could never allow anyone to see that she and her baby were getting more and more sick, that they were dying.

If she did this, she would become a Swazi woman with HIV, an HIV-positive child, and no family or other financial support. She would be alone.

We spoke of her alternatives. We spoke of her strengths. We scheduled her next visit, when she would bring with her an ally from her community, in secret if necessary, to learn about the medicines and how to give them. With this support, Thembela and her child are much more likely to be able to properly store and dose the medicines without being discovered.

“You do not have to do this alone,” I said. “Your baby is going to grow up, and she will need you to take care of her.”

Three weeks later, Thembela has a thriving business selling chicken and rice lunches in front of our clinic. She sells a few dozen such meals daily, for six Lilanginis each (approximately 90 cents). She is planning to use the profits to rent a room down the road from the clinic, where she will cook lunches, raise her child, and keep her ARVs.

I eat her lunch every day. Some days the chicken and rice come with greens and potatoes, some days beetroot, others spinach. Delicious.

“Remember me?” she asked when I saw here outside of the exam room for the first time. “I am your first patient.” I said that I remembered very well, searching my pockets for coins. “I am saving the life of my child,” she said, smiling.

I smiled back.

Well played, Thembela.

Labels: Patient encounters

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home